[Editor’s note: Bring your imagination and an appetite for big, big questions in this seminar on two books by Han Kang, the 2024 Nobel Laureate for Literature. If you’ve wanted to shake up your fiction reading with novels that truly feel new and different, this is the seminar for you!]

All that live eat. Do all that eat live? What is living?

Tennyson’s bracing description of Nature, “red in tooth and claw,” is embedded in a twelve-and-a-half-line question about “Man”:

And he, shall he,

Man, her [i.e., Nature’s)] last work, who seemed so fair,

Such splendid purpose in his eyes,

Who roll’d the psalm to wintry skies,

Who built him fanes of fruitless prayer,

Who trusted God was love indeed

And love Creation’s final law —

Tho’ Nature, red in tooth and claw

With ravine, shriek’d against his creed —

Who loved, who suffer’d countless ills,

Who battled for the True, the Just,

Be blown about the desert dust,

Or seal’d within the iron hills? (1)

Must human beings obey the remorseless law of “tooth and claw?”

Must not justice follow the logic of Lincoln’s statement about slavery, “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master”? (2) Which, when applied to eating, would go something like, “As I would not be killed, so I would not kill, for to eat is to destroy and to destroy is to kill?”

Is there no way around so dismal a dichotomy? Is there no false choice that may be recognized and transcended? Is not the declension from cannibalism to eating deer and rabbits and chickens to eating tomatoes and soybeans and lettuce a happy and salutary one? But are not plants, too, alive?

Is there no way around so dismal a dichotomy? Is there no false choice that may be recognized and transcended? Is not the declension from cannibalism to eating deer and rabbits and chickens to eating tomatoes and soybeans and lettuce a happy and salutary one? But are not plants, too, alive?

However happy the sliding scale down and away from cannibalism, it seems one cannot take a step in any direction without touching the metaphysic of this moral or the moral of this metaphysic, for we cannot, as Hamlet says, “eat the air promise-cramm’d.” (3)

With the elements of our being, and of our being together, Han Kang begins her breathtaking novels The Vegetarian and Greek Lessons. Food, touch, sex, birth, child, air, light, movement, sound, sight, speech, voice, woman, man, word, letter: what is each of these? What is it to live in and with them? What might it be to live without them?

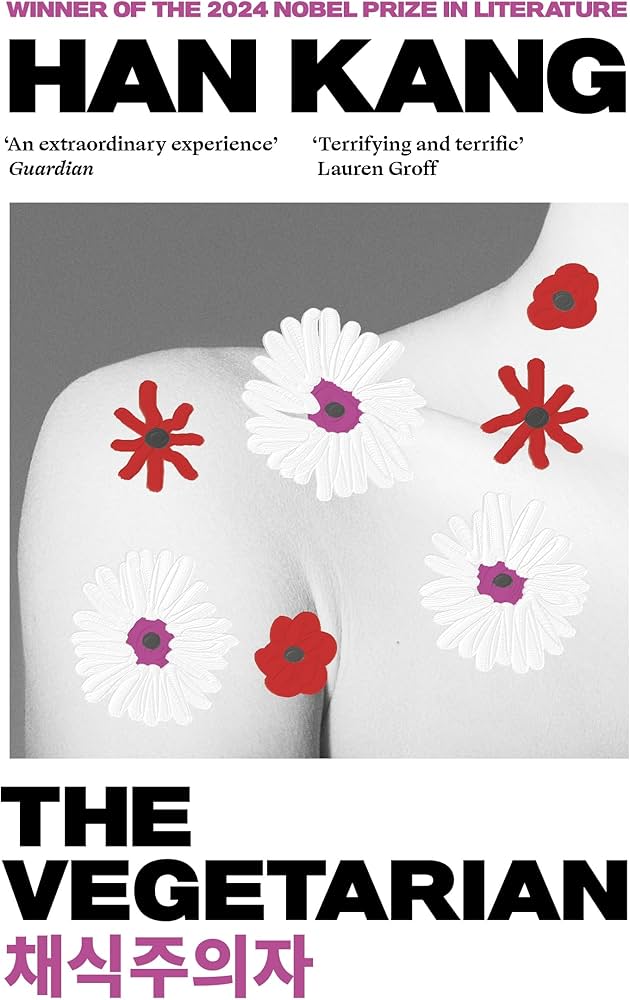

In the first novel we’ll discuss, The Vegetarian, a woman tries to live out, in her own life and in her own body, a response to the problem of violence and thereby undergoes a modern metamorphosis according to a radical moral physics in which humanity may be achieved by dissolving the human being. Or is it not humanity at all, but only an illusion thereof? Or was the human being the illusion to begin with? What is really human? What is really being?

In the first of the novel’s three parts, the woman, in a kind of reverie, thinks, or utters to herself, or dreams:

Can only trust my breasts now. I like my breasts, nothing can be killed by them. Hand, foot, tongue, gaze, all weapons from which nothing is safe. But not my breasts. With my round breasts, I’m okay. Still okay. So why do they keep on shrinking? Not even round anymore. Why? Why am I changing like this? Why are my edges all sharpening – what am I going to gouge? (4)

And in the second third of the book, of a man related to this woman by marriage and suddenly intensely attracted to her, we hear:

He was becoming divided against himself. Was he a normal human being? More than that, a moral human being? A strong human being, able to control his own impulses? In the end, he found himself unable to claim with any certainty that he knew the answers to these questions, though he’d been so sure before. (5)

In Greek Lessons, Greek letters are chalked on a board, Greek syllables made to flutter through the Korean air, until they aren’t because they can’t be, at least by the one who had been making those things happen. The hearer/student, once a teacher, writes them into her hand. But she cannot speak back to him who writes them on the board, for her teacher soon will be unable to see even the character of the human face out of which the voice he has never heard has long ceased to sound.

In Greek Lessons, Greek letters are chalked on a board, Greek syllables made to flutter through the Korean air, until they aren’t because they can’t be, at least by the one who had been making those things happen. The hearer/student, once a teacher, writes them into her hand. But she cannot speak back to him who writes them on the board, for her teacher soon will be unable to see even the character of the human face out of which the voice he has never heard has long ceased to sound.

From a dead language, no matter how incomparably beautiful, what lessons may be learned by a blind reader or discussed with an undeaf mute? Near the middle of the story, at the start of a lesson, we hear of a pun by Socrates on “pathein mathein,” the verbs meaning “suffer” and “learn.” We are reminded that through the same organ by which we ingest and speak and sometimes breathe we also kiss. The ghost of Borges, fittingly, haunts the novel.

Join me at Toronto Pursuits this July for Planting Humanity: Two Novels of Han Kang.

– Eric

Eric Stull teaches English at colleges and universities in Maryland and the tri-state area. To learn more about him, see our interview with Eric on YouTube.

Sources:

1. In Memoriam, 55.

2. Fragment variously entitled “On Slavery and Democracy” or “Definition of Democracy,” conjectured to have been written in 1858.

3. Hamlet, 3.2.90.

4. The Vegetarian, Smith translation, Hogarth Press, 2015, p. 39.

5 .Vegetarian, p. 67.

6. Greek Lessons, Smith and Yaewon trans., Penguin, 2023, p.66.

Featured image credit: PickPik