One of my daughter’s favorite singers, Hozier, wrote a popular song called “Wasteland, Baby!” Here are some lyrics from the single:

And that day that we watch the death of the sun

That the cloud and the cold

And those jeans you have on

And you gaze unafraid

As they sob from the city ruins

Wasteland, baby

I’m in love, I’m in love with you

I also recently read a fantasy novel I enjoyed, set in an alternative version of the early 20th century, called The Curious Traveler’s Guide to the Wastelands. The story imagined a Siberia where the landscape had become so hostile to human beings that it could only be viewed from a fortified train. There’s even a famous video game called “Wasteland” from 1988, set in a time after a nuclear holocaust.

Why are these stories popular with millions of people? And why is the word “wasteland” so evocative?

Before 1922, the use of the word (or two words) was fairly rare and mainly referred to “barren or uncultivated land” (according to the Online Etymology Dictionary—the Oxford English Dictionary hardly even mentions it). After the publication of Eliot’s poem, usage began to increase, and it continues to be more and more popular today. According to Merriam Webster, meaning has shifted to include either “an ugly, often devastated, or barely inhabitable place or area,” or “something: (such as a way of life) that is spiritually and emotionally arid and unsatisfying.”

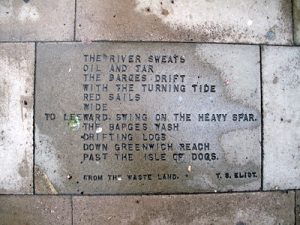

in London’s South Bank

It seems Eliot’s poem caused the word to begin to be associated with our modern obsessive imagining of a post-apocalyptic earth, and it yoked together the image of desolate land with the feeling of a desolate soul. There’s a great deal of fortune-telling in the poem, so perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that as a work of art it also has a prophetic quality.

People have been drawn to stories of apocalypse since ancient times, of course. We see it in Jeremiah and Isaiah, Ragnarok, and the Book of Revelation. In Eliot’s time there were many writers such as H.G. Wells and William Morris trying to imagine how the current world might end and something different begin. They warned of catastrophe ahead or offered visions of a new and better way of life waiting after this one was destroyed.

Eliot’s unique attitude was one of grief, the apprehension that everything precious had been destroyed already … and yet somehow it was possible to create poetry. As a woman asks in the poem, “Are you alive, or not?” Is that what the poem asks us to consider of ourselves and our “land?” What has been laid waste within us? What would it mean to be alive if we’re not?

These are some of the questions we will investigate during our seminar in Toronto, examining “The Waste Land” as an exploration of symbols of spiritual and cultural devastation that have become ubiquitous in the century since it was written.

Image credit: Duncan Cumming on Flickr