Bibliothèque Nationale de France

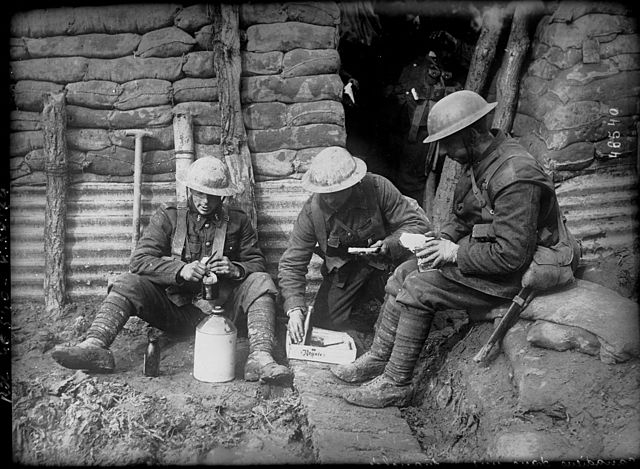

What happens when large numbers of literate soldiers are “plunged into inhumane conditions?” (1) World War I was the first global conflict in which (with some exceptions) most soldiers could read and write. The result was an outpouring of novels, memoirs, plays, songs, and above all, poetry. More than 2,000 British and Irish poets wrote war poetry. (2) Writing alongside them were soldiers and civilians from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Caribbean, South Africa, the United States, France, Germany, Italy, Turkey—the list goes on, stretching across the world.

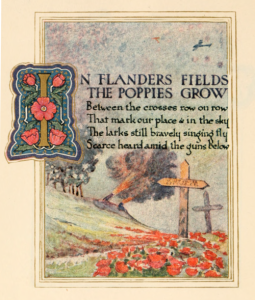

Most of these poets are long forgotten, and even among those still read just a few of their most anthologized works linger in our memories. These few poems have had, however, an enormous influence on how following generations have thought about World War I. In The Price of Pity, Martin Stephen puts forth that “society’s vision of this historical event … was ironically determined by a literary response to it, and it is the vision of some of the war’s poets that has dominated the popular image of what the war was to those who fought in it and lived through it.” (3) You have perhaps had snatches of these poets’ verses run through your head since you started to read this post: John McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields”, Rudyard Kipling’s “For All We Have and Are” and Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est”.

In my online seminar on WWI poetry, which starts September 16, we will read some of these poems that have remained so compelling. But we will also look at a broader range of works that add to Stephen’s “popular image,” often simplified to the idea of patriotic poems vs. antiwar ones. Holding too closely to our received ideas about war poems makes us deaf to their words. In the view of Santanu Das, “First World War poetry often ceases to be poetry and begins to look like history by proxy …. First World War poetry represents one of those primal moments when poetic form bears most fully the weight of trauma. Art and testimony are often yoked together by real-life violence, leading to formal realignment, invention or dissonance. Categories such as ‘pro-war’ and ‘anti-war’ often prove inadequate, when tested against the complexity of individual poems.” (4)

These works include soldier-poet Charles Sorley’s haunting When You See the Millions of Mouthless Dead, nurse Mary Borden’s, and James Weldon Johnson’s

Poems, well known and not, that evoke despair, anger, joy, and outrage. Poems that speak of beauty, cruelty, death, loneliness, desire, and love. As we peel back the layers that time, other wars, and shifting global orders have placed between us and these poets, we’ll each build a more nuanced understanding of what World War I meant to those who lived it.

Join me September 16 for Poetry of World War I.

— Melanie

Sources:

- Stuart Lee, An Introduction to WWI Poetry (http://ww1lit.nsms.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/education/tutorials/intro/intro)

- Santanu Das, “Reframing First World War poetry” (https://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/reframing-first-world-war-poetry)

- Martin Stephen, The Price of Pity, 1996, p. xii

- Santanu Das