[Editor’s note: Who am I and what can I know? Join artist Sean Forester at Toronto Pursuits this summer to explore this most fundamental of questions through the lens of Shakespeare, Montaigne, and a wonderful range of men and women artists.]

“Look in thy glass, and tell the face thou viewest …” — Shakespeare

When we look into the mirror, what do we see? How do we present ourselves to the world? Who are we really?

These are some of the questions we will try to answer through art, literature, and philosophy this summer in Toronto in my seminar Man in the Mirror: Self-Knowledge in Montaigne, Shakespeare, and Rembrandt.

Here is Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait with Two Circles (1665–1669). At the time he painted this work, Rembrandt was in his sixties and had suffered crushing loss: the death of his wife and children, bankruptcy, and the ensuing loss of his artistic reputation, house, and belongings.

You can see suffering in his face, but he stands with simple dignity, looking at us directly. Rembrandt holds his tools of work: palette, brushes, and maulstick. His searching gaze is matched by the experimental way the paint is applied. This portrait is an encyclopedia of painting techniques: impasto, loose and broken brushwork, dry brush, scumbling [a technique used to make color less brilliant by covering it with a thin coat of opaque or semiopaque color applied with a nearly dry brush], glazing, and even scraping with the brush handle (you can see this on the left eyebrow).

What is the meaning of the circles behind the artist? Do they represent hemispheres, a Dutch map of the world? Are they symbolic, the Greek sense of a perfect underlying geometry to reality? Or is Rembrandt alluding to the legend of how the Pope sent a message to ask artists to submit a sample of their work to see who would be offered an important commission, and Giotto took a piece of paper, drew a perfect circle freehand, and gave it to the messenger?

In addition to Rembrandt’s work, we will discuss self-portraits across the centuries by artists ranging from Albrecht Dürer to Frida Kahlo and Jenny Saville. For a preview, take a look at this slide show. Isn’t it remarkable the variety of how the men and women present themselves?

When we look at ourselves in the mirror, we perceive both a face and a mind. Our image may give rise to thoughts and feelings, to self-examination. And what better author for this than Shakespeare? We will read Hamlet and selected sonnets. Hamlet, arguably the greatest play in the English language, needs no introduction, but here is Kenneth Branagh performing the “To be or not to be” soliloquy in front of a mirror.

When we look at ourselves in the mirror, we perceive both a face and a mind. Our image may give rise to thoughts and feelings, to self-examination. And what better author for this than Shakespeare? We will read Hamlet and selected sonnets. Hamlet, arguably the greatest play in the English language, needs no introduction, but here is Kenneth Branagh performing the “To be or not to be” soliloquy in front of a mirror.

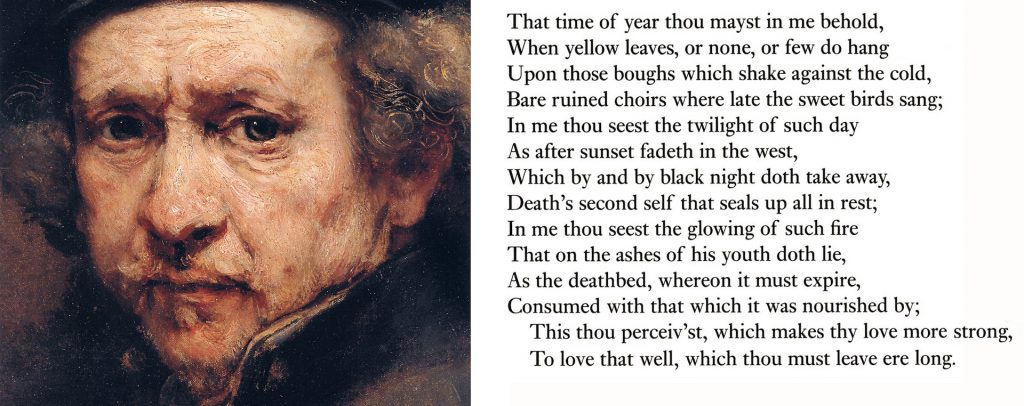

In Shakespeare’s sonnets, the mirror can be the person to whom the poem is addressed (the beloved) or it can the reader, who acts as a mirror for the poet to examine him- or herself. Sonnet 73 is one my favorites. Shakespeare has such abundance of language and metaphor.

Consider the third line of first stanza: “Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.” This line creates an image of a row of trees that appear like a cathedral, with the trunks as columns and bare branches as a Gothic tracery vault. In Shakespeare’s time, many of the English abbeys lay in ruins like bare trees because Henry VIII had dissolved the monasteries when he broke away from the Catholic church. The songbirds have migrated south, the choir boys returned to Rome.

Or take the second line: “When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang.” Most of us would have written, “When yellow leaves, or few, or none, do hang.” That’s a logical order, but the inversion is brilliant: It paints a picture of just a few stragglers hanging on. Shakespeare invites us to imagine him in old age, with skin falling off like the yellow leaves. Looking into the mirror, the poet faces his own mortality. The structure of the poem itself embodies this: The first stanza describes the seasons (a year), the second twilight (a day), the third a fire (an hour). Classically, the sonnet has a “turn” after line 8, dividing the poem into 8, 6 as well as 4, 4, 4, 2. The first part of the poem is melancholy with poet’s life “fading.” But then there comes the turn. By using a “glowing” fire in line 8, the tone changes, and we are prepared for the affirmation of the final couplet:

This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

That’s a preview of some of riches we will discover in Toronto this summer. In addition to Shakespeare, we will read Montaigne, the original essayist. I’ll explore Montaigne in an upcoming blog. As the English writer William Hazlitt says, “[Montaigne] was the first who had the courage to say as an author what he felt as a man.”

I do hope you will join us for Man in the Mirror: Self-Knowledge in Montaigne, Shakespeare, and Rembrandt . I’ll even promise to bring my own self-portrait!

– Sean

Latest Updates

Seminars on literature from the ancient world to today

See the world through the eyes of visionary writers and artists

An annual gathering of lifelong learners