By Betty Ann Jordan

The text I’ve chosen for the 2015 Classical Pursuits art session is by Peter Schjeldahl, a poet turned art reviewer, initially for the Village Voice, and then for the New Yorker. In the mid-’90s, while I was an editor at Canadian Art magazine, we published a feature review by Peter Schjeldahl not long before he joined the New Yorker’s pantheon of contributors. His crisp copy required no editorial fixes at our end, but something shifted in me. I fell hard for his conversational tone, sparkling language and fresh insight. My exhilaration at having found a model for my own nascent professional art writing has never wavered.

The text I’ve chosen for the 2015 Classical Pursuits art session is by Peter Schjeldahl, a poet turned art reviewer, initially for the Village Voice, and then for the New Yorker. In the mid-’90s, while I was an editor at Canadian Art magazine, we published a feature review by Peter Schjeldahl not long before he joined the New Yorker’s pantheon of contributors. His crisp copy required no editorial fixes at our end, but something shifted in me. I fell hard for his conversational tone, sparkling language and fresh insight. My exhilaration at having found a model for my own nascent professional art writing has never wavered.

Leavened by humour, Peter Schjeldahl takes a journeyman’s attitude towards his rarefied profession: (“Writing about mute objects feels like honest work,”) adding, “If you get the objective givens of a work right enough, its meaning (or failure or lack of meaning) falls into your lap.”

His essays inspire waves of recognition and recollection of prior visual experiences cherished but never articulated. He also makes the processing of art seem natural, implying that any observant and well-intentioned person not only could do it but should do it to get more out of life. “Responding to art works we rehearse attitudes towards anything that matters,” he says.

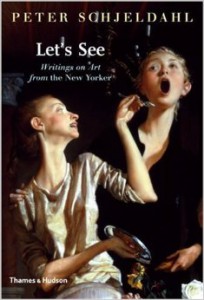

Many of the essays in Let’s See centre on major historical exhibitions, ranging from Manet and Picasso to Sexy Surrealism. Schjeldahl suggests that one’s art-historical foreknowledge (or lack thereof) should not be an impediment to understanding and visceral pleasure. Always respectful of the integrity of objects, he says: “I want to say the most interesting and entertaining things a work lets me say and nothing it doesn’t.”

Allusive and idiosyncratic, he knocks the stuffiness out of communing with the Old Masters such as Rembrandt, whom he tags as a detective. “Once exposed by the master, mysteries become as plain as day,” says the critic. “A mystery for Rembrandt may take the simple form of what something he has not experienced is like, for example, ‘What is it like to commit murder?’”

Schjeldahl takes art personally, seeing it as an inducement to better living: “Matisse gets quietly drunk on visual seduction and induces in viewers a contact high, making you hate your life for its comparatively insipid joys.” And he can be earthy: “Cezanne showed how to bring about a tiny climax with just about every brushstroke.”

The writer is honest to the point of bluntness: When asked about how he engages with new, unfamiliar art for which he doesn’t yet, (or may never) feel a strong affinity, he says: “I build a large lawyerly case that justifies the work’s existence, character and consequence. I take professional pride in being able to do this, just not too often. Nothing ruins a critic like pretending to care.” Ouch! Softening, however, he adds a compelling rationale for spending time with art you don’t like: “If you don’t consent to understand a little, on its own terms, what you dislike, your love loses muscle tone.”

Regarding his taste in literature, Schjeldahl favours the classics which—unlike much of the contemporary writing he’s read and respected—induce in him an enthusiasm that he associates with “the feeling that a stranger has written a book with me alone in mind.”

This July in Toronto, one hopes a similar conviction that this book has been written for us alone will inform our group’s analysis of several pre-assigned essays per day, including his revealing Twenty Questions introduction. We will also attend one major art exhibition together on the Wednesday, with the option of writing (and sharing with the group) a short review of that exhibition on Friday, our final day together.

Click here for more information and to register. Guided by our new friend, Peter Schjeldahl, together let’s see how best to use art to leverage more out of life.

– Betty Ann

Photo credit for portrait of Peter Schjeldahl: Interview magazine

Latest Updates

Seminars on literature from the ancient world to today

See the world through the eyes of visionary writers and artists

An annual gathering of lifelong learners

A 2022 participant

June G.

Attendee since 2013