We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

– T.S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

What is the nature of art and the artist? Is art to be pursued through order, control, individuality, and sober thought, or is it more apt to be found in irrationality, ecstasy, anti-intellectualism, and unrestrained expression of emotions? Can these seemingly opposing forces coexist within a person?

These are the questions that preoccupied Thomas Mann, who is widely acknowledged as the greatest modern German novelist, in his novella, Death in Venice. The novella is based on Mann’s own trip to Venice in 1911: Mann reflected that “nothing was invented—everything was given.” The story’s protagonist, the aging German writer Gustav von Aschenbach, is presented as honourable, disciplined and dedicated to his art. He believes that true art requires him to refrain from expressing passion in either in his life or his art. Struggling with writer’s block, Aschenbach travels to Venice in hopes of rekindling his artistic inspiration.

The questions that fascinated Mann are ones we will explore together during our week at Toronto Pursuits this July. We will also examine the metamorphoses of this work into film and opera. Sixty years after its publication Mann’s novella inspired two almost equally famous adaptations, Luchino Visconti’s visually ravishing 1971 film Death in Venice and Benjamin Britten’s striking 1973 opera.

The questions that fascinated Mann are ones we will explore together during our week at Toronto Pursuits this July. We will also examine the metamorphoses of this work into film and opera. Sixty years after its publication Mann’s novella inspired two almost equally famous adaptations, Luchino Visconti’s visually ravishing 1971 film Death in Venice and Benjamin Britten’s striking 1973 opera.

I am a musician and composer and a long-time student of Thomas Mann and Gustav Mahler. Back in 2000 at Toronto Pursuits and again in 2009 on location in Venice with Travel Pursuits, I was thrilled to share the insights of our seminar members as we discussed these three works, investigating both how Gustav von Aschenbach’s metamorphosis can be understood and the ways in which Visconti and Britten appear to agree or quarrel with Mann’s own views. As with all great art, each time I come to the original or one of the adaptations, I see it in a different way. And the observations of my fellow travellers always offer exciting new discoveries.

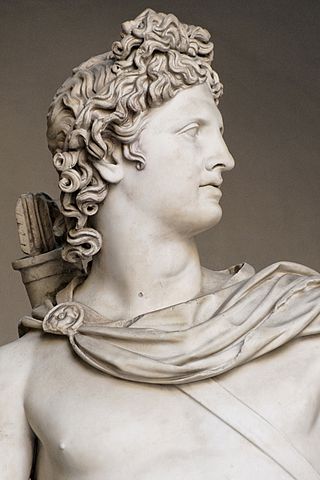

Whether you have read little or much Thomas Mann, whether you are an opera-goer or not, I feel sure you will find great pleasure in these wonderful works and in the stimulating discussion they will inspire. You can click on the link to learn more about my seminar, Death in Venice: A Modern Contest between Apollo and Dionysus. I’ll look forward to meeting you at Toronto Pursuits 2016!

– Tom

Photo credits: Belvedere Apollo detail Marie-Lan Nguyen; Dionysus, Jerry and God